The Greek and Roman Inscriptions

on the Obelisk-Crab in the

Metropolitan Museum,

New York

This slim volume about the Greek and Roman inscriptions on the claw of the obelisk-crab in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (written by A. C. Merriam) was published in 1883 and reprinted in the beginning of the 21st century. It is a fascinating case story about how to handle ancient evidence.

Augustus

Chapman Merriam (1843-1895) was a classical scholar from the US Columbia College

An

obituary, by Clarence H. Young, appears in the American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 10, # 2, April-June 1895, pp. 227-229.

What is an

obelisk-crab and how did a Roman crab from Egypt New York

Two ancient

Egyptian obelisks are known as Cleopatra’s Needles, even though the famous

queen did not have anything to do with them. They were commissioned and erected

in Heliopolis Egypt Alexandria

Around AD

1500 one of the two obelisks fell down, while the other remained standing. In

1877 the prostrate obelisk was dug up and transported to England

When the

first obelisk was removed from Alexandria, the foundation of the other was cleared, and this is

when the crabs were discovered. Only two crabs and one claw remained, the rest

had disappeared. There was no trace of the four crabs which had supported the

London Obelisk. Two inscriptions were carved on the claw: in Greek on the

outside, in Latin on the inside. At the time of discovery the crab was almost

two thousand years old, and the letters were not easy to read. The first

reading of the Latin text gave the following result:

ANNO VIII

CAESARIS

BARBARUS

PRAEFAEGYPTI POSUIT

ARCHITECTANTE PONTIO

In English:

“In year 8 of Caesar the governor Barbarus erected [this obelisk] in Egypt

The Greek text

seemed to give the same information (see more below).

Octavian (later known as Augustus)

conquered Egypt

The other Alexandrian

obelisk was taken down in 1879, transported to the US New York Central Park in 1881. The project was supervised by Henry H. Gorringe,

a former Lieutenant-Commander of the US Navy, who handed the two crabs and the

claw over to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (colloquially known the the Met). For the New York Obelisk four new crabs with eight claws

were cast at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in order to re-create the ancient Roman setting.

The crabs are

huge: one modern replica weighs ca. 900

pounds . You can find some great pictures of them on the internet. The website Scouting New York has a detailed report about The Oldest Outdoor Man-Made Object in New York.

The first reading of the inscriptions was used by James King in Cleopatra’s Needle (1883, 1886, 1893) and by Henry H. Gorringe in Egyptian obelisks (1882).

Several

scholars defended the first reading, including the famous German scholar

Theodor Mommsen (1817-1903). In order to do this, Mommsen had to “bend” the evidence:

he had to follow the Greek author Dio, who wrote two hundred years after these events, and he

had to reject the Greek author Strabo, who was a contemporary witness. Not exactly Mommsen’s

finest hour.

In 1883,

when Merriam came to the Met to study the original evidence, he quickly

realised that the first reading was wrong, because the date (year 8) and the

name of the governor (Barbarus) did not match each other:

** The

first governor Cornelius Gallus served 30-26 BC

** The

second governor Petronius probably served 26-20 BC

** The

third governor Aelius Gallus probably served 20-18 BC

The date

23-22 BC does not fit any of them (page 17).

But a governor

called Publius Rubrius Barbarus is known from a Greek inscription in the temple

for Augustus on the island of Philae

Merriam

went back to the Met and asked the staff to clean up the claw, and step by step

everything fell into place:

During the

second reading of the Latin version the date became clear: ANNO XVIII. Not 8,

but 18: the same year as the inscription from Philae !

The first

reading of the Greek version began with the letters L H, where the Roman letter L stands

for “year” and the Greek letter H for the number 8. During the second reading

of the Greek version the date became clear: L IH, where the letters IH stand

for the number 18. The same year as in the Latin version!

Amazingly,

the first reading of both versions gave year 8 or 23-22 BC, which does not

fit the evidence at all, while the second reading of both gave year 18, or 13-12 BC,

which fits the evidence perfectly.

The

correct versions appear in C. E. Moldenke, The New York Obelisk: Cleopatra's Needle (1891) and in E.

A. Wallis Budge, Cleopatra’s Needles and Other Egyptian Obelisks (1926).

Merriam’s diligence

and patience had paid off. The mystery was solved. And now, he says, we can understand the

emperor’s line of thought: moving two (relatively small) obelisks from Heliopolis Alexandria Egypt Rome

Several

scholars studied the ancient inscriptions on the Roman claw; and several

scholars got it wrong. Merriam got it right. That is why his essay about the

obelisk-crab in the Met is still important and valuable.

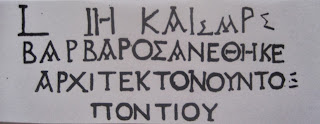

The Greek inscription is carved on the outside of the claw (seen in this picture).

The Latin inscription is on the other side of the claw.

The Greek inscription carved on the outside of the claw covers

an area of ca. 8 x 4 inches (four lines).

The Greek inscription written with regular Greek letters (four lines).

The Latin inscription carved on the inside of the claw covers

an area of ca. 6 x 3 inches (four lines).

The Latin inscription as it appears in Merriam's essay.

(above) The first reading (four lines)

(below) The second reading (two lines)

The Greek inscription as it appears in Merriam's essay.

(above) The first reading (four lines)

(below) The second reading (only one line)

* * *

No comments:

Post a Comment