Cleopatra’s

Needle and Other Egyptian Obelisks by E. A. Wallis Budge was published by the

Religious Tract Society in 1926 and reprinted by Dover

Ernest

Alfred Wallis Budge (1857-1934) was a well-known British orientalist: Keeper of

the Assyrian and Egyptian Department of the British Museum

In his

preface he explains: “This volume … is intended to replace the little book ‘Cleopatra’s

Needle’ written by the late Rev. James King” and published towards the end of

the 19 century.

The main

text is divided into two parts:

The first

part covers the same ground as King’s book. The author gives a general

presentation of the ancient Egyptian obelisk and explains how the obelisk known

as Cleopatra’s Needle was moved to London

The second

part gives a lot more than we find in King’s book. The author presents all the

important Egyptian obelisks. Some of them are still in Egypt Rome Constantinople (today Istanbul New York

A brief

bibliography and an index are placed at the end of the book. The text is

illustrated with 22 drawings and 17 black-and-white photos.

In King’s

book the hieroglyphs are printed in a vertical line, exactly as they appear on

the ancient monument, going from top to bottom. Moreover, the hieroglyphs are

explained one by one, so the reader can see how the English translation is

created (step by step). This system is very helpful, very pedagogical.

Unfortunately,

Wallis Budge often has another approach: in his book the hieroglyphs are usually

printed in horizontal lines, going from left to right. Moreover, the hieroglyphs

are not explained one by one; instead there is a large block of hieroglyphs (five,

six or seven lines) followed by an English translation of this block. This

means that the reader cannot see how the translation is created.

Some sections

are more successful than others. One of the most successful is the section

about the obelisk of Hatshepsut (pp. 98-124), which includes four full-page

drawings of the vignettes on the upper part of the obelisk. The long

inscription on the base of the obelisk is quoted in full. The lines of

hieroglyphs are numbered (from 1 to 32), and these numbers are repeated in the

English translation, so the reader can compare one with the

other.

Perhaps the

least successful is the section about the speech of Amen-Ra (pp. 130-142). The

lines of hieroglyphs are numbered (from 1 to 25), but these numbers are not repeated

in the English translation, so it is almost impossible for the reader to

compare one with the other.

This text

is also found in First Steps in Egyptian: A Book for Beginners written by Wallis

Budge and published in 1895 (pp. 156-167). And what a surprise it is to go back

in time: in this book the hieroglyphs are explained one by one, exactly as they

should be.

Wallis

Budge is an expert who knows his topic very well, but sometimes he is a bit careless

with the details. Here are some examples:

(1) In his

preface (page viii) he claims King visited Egypt Palestine

(2) The

caption to Plate II facing page 42 says: “Scaffold built by Fontana Rome

(3) On page

48 we are told: “… in 1836 [the French engineer] Le Bas was deputed to go out

and dismount the obelisk chosen by Champollion and … re-erect it in Paris Paris

(4) On page

167 we are told an Egyptian obelisk was “transported … to New York 1880 in the Central Park by Lieut.-Commander H. H.

Gorringe.” In fact, this obelisk was taken down in 1879, transported to the US Central Park in 1881. [The correct dates appear

in a footnote on page 55.]

(5) On page

182 we are told Augustus conquered Egypt Egypt

(6) Egyptian Obelisks by Lieutenant-Commander Henry H. Gorringe is mentioned

several times; each time we are told this book was published in 1885. But the

correct date is 1882.

Sometimes

Wallis Budge does not give us the whole story: the obelisk standing next to San

Giovanni in Laterano (St. John Lateran) in Rome

All four inscriptions

are given - in Latin and in English - in Tyler Lansford, The Latin

Inscriptions of Rome (2009) (pp. 226-231).

In spite of

the flaws mentioned above, this old book by Wallis Budge is still interesting and

valuable, because it provides an almost complete record of the inscriptions on the

ancient Egyptian obelisks.

The facade of San Giovanni in Laterano (known in English as St. John Lateran),

the first Christian church in Rome, built 314-318,

during the reign of Constantine (306-337).

Detail of the facade.

The ancient monolith, known as the Lateran obelisk, is standing on a modern pedestal.

Today it is 32 m tall. In antiquity it was a bit taller. A Christian cross is placed

on top of it to show that the Christian religion (with one god) is stronger

than the pagan religion of ancient Egypt (with many gods).

Detail of the ancient Egyptian obelisk.

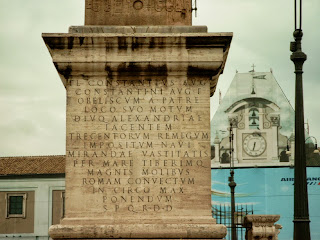

The modern pedestal is decorated with a Latin inscription on all four sides.

This picture shows the inscription on the east side (15 lines).

The Latin text:

FL CONSTANTIUS AUG / CONSTANTINI AUG F / OBELISCUM A PATRE / LOCO SUO MOTUM / DIVQ ALEXANDRIAE / IACENTEM / TRECENTORUM REMIGUM / IMPOSITUM NAVI / MIRANDAE VASTITATIS / PER MARE TIBERIMQ / MAGNIS MOLIBUS / ROMAM CONVECTUM / IN CIRCO MAX / PONENDUM / SPQR D D.

In English:

"Flavius Constantius Augustus, son of Flavius Constantine, gave to the Senate and People of Rome as a gift to be placed in the Circus Maximus the obelisk moved from its site by his father and long neglected at Alexandria, set aboard a 300-oared ship of astonishing size, by mighty labours

conveyed across the sea and up the Tiber to Rome."

In 1607 a fountain was placed at the foot of the ancient obelisk. It was built by Paul V,

who was pope 1605-1621. The fountain is decorated with an eagle

flanked by two dragons. This motive is borrowed

from the pope's coat of arms.

The ancient monolith weighs more than 450 tons. Today its height is 32 m.

If we add the modern pedestal below and the Christian cross on top,

the total height of the monument is 46 m.

The obelisk was commissioned by Thutmose III ca. 1450 BC. It was completed and erected

in the Karnak temple complex by his grandson Thutmose IV ca. 1400 BC.

Around AD 330 the obelisk was moved from Karnak to Alexandria where it was left for

several years. In AD 357 it was transported to Rome where it was

placed on the spina of the Circus Maximus. It was

erected in its present position in 1588.

Detail of the obelisk.

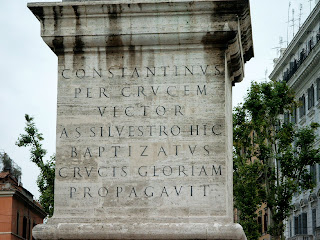

The modern pedestal is decorated with a Latin inscription on all four sides.

This picture shows the inscription on the south side (seven lines).

The Latin text:

CONSTANTINUS / PER CRUCEM / VICTOR / A S SILVESTER HIC /

BAPTIZATUS / CRUCIS GLORIAM / PROPAGAVIT.

In English:

"Constantine, through the cross victorious, baptized in this place by

Saint Silvester, furthered the glory of the cross."

The information given in this inscription is not true:

Constantine was not baptized by Saint Silvester at Rome.

Pope Sylvester died on 31 December 335. Constantine was baptized at

Nicomedia (today Izmit) by Eusebius on 22 May 337, just before his death.

* * *

No comments:

Post a Comment