The Problem of the Obelisks:

From a Study of the Unfinished

Obelisk at Aswan

The

Problem of the Obelisks by R. Engelbach, published by T. Fisher Unwin Ltd. in

1923, was reprinted by Nabu Press in 2010 and by Forgotten Books in 2012. This

old book is still interesting and valuable.

Reginald (or

Rex) Engelbach (1888-1946) was a British Egyptologist. On the title page of this book he is described as Chief Inspector of Antiquities in Upper (i.e. southern) Egypt

I –

Obelisks and Quarries

II –

Description of the III - Setting out an Obelisk

IV –

Extraction of an Obelisk

V –

Transport of an ObeliskVI – Erection of an Obelisk

VII – Some

ancient Records

VIII - A

History of certain Obelisks and their ArchitectsIX – Removals of Obelisks in modern Times

At the end

of the book we find Appendix I (Dates of Egyptian kings) and Appendix II (Spelling

of Egyptian names) and a general index. The text is illustrated by 44 photos

and drawings in black-and-white.

As you can

see from the table of contents, this is not a traditional book about ancient

Egyptian obelisks. The focus is on the mechanical and technical problems

related to obelisks, and the starting point is the broken or unfinished obelisk,

which is still lying in the ancient quarry at Aswan Egypt

The

subtitle – From a Study of the unfinished Obelisk at Aswan

In his

preface Engelbach explains that this volume (published in 1923) is a popular

version of a scholarly report The Aswan Obelisk (published in 1922). The

popular version is an easy read. The technical stuff is not difficult to

understand. The text and the illustrations complement each other well. The illustrations

help the reader understand the point he is trying to make in the text.

Unfortunately, illustrations

are not always placed next to the relevant passages in the text. You have to

flip back and forth between text and illustration. This is a bit annoying,

but it is only a minor problem.

The Aswan 137 feet long. If it had been completed, the

weight would have been ca. 1,168 tons. It would have been the tallest and the

heaviest obelisk in the world.

The workers

had to give up, because they found several fissures in the granite. They tried

to evade this problem and create a smaller obelisk instead, but even this plan had to be abandoned, because

the fissures were too widespread.

We do not

know when this took place; perhaps around 1500 BC, but the ancient obelisk is

still lying in the ancient quarry, and when we study this unfinished project,

it is possible to find the answer to some of the questions that we have about

the ancient obelisks (chapters I and II).

In chapters III-VI the author follows an obelisk step by step from the moment when it is excavated in the quarry until it is standing in front of an ancient temple. The author presents and evaluates several interpretations of the material evidence. In some cases he has even conducted a practical experiment on a small scale. As far as I can see, his account is reliable, and his conclusions are sound.

In chapter

VII he reviews the ancient literary evidence about obelisks, which is quite

limited. The Egyptians set up many obelisks, but they never bothered to give us

a detailed account about how it was done. That is why the methods employed are

still the subject of intense discussion today.

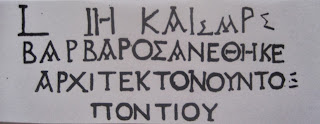

In chapter

VIII the author presents some of the royal architects, who worked for the

pharaohs. We know some names and sometimes a bit more about them, because they

were buried in individual tombs in Thebes. Here are a few examples:

** Ineni, who

worked for Thutmosis I, was buried in a tomb known as TT 81.

** Sennemut,

who worked for Hatshepsut, was buried in a tomb known as TT 71.

** Other

architects are Dhutiy (TT 11); Puimre (TT 39); Menkheperra-sonb (TT 86); and

Beknek-honsu (TT 35).

Ancient

Egyptian names are tricky, because they were written without the vowels. Modern

scholars do not always use the same forms as Engelbach did in the beginning of

the 20th century. For instance he says Hatshepsowet, while modern

scholars say Hatshepsut.

When discussing how a heavy monument was moved on

land, Engelbach refers to a wall painting found in the tomb of Dhuthopte in

el-Bersheh. Modern scholars call this person Djehutihotep and the location Deir

el-Bersha.

In chapter

IX the author completes his account by telling us the story of four famous obelisks,

which were erected in foreign lands in modern times:

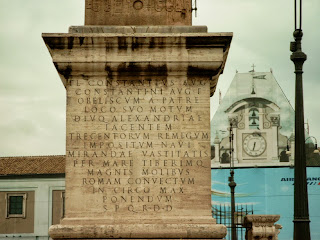

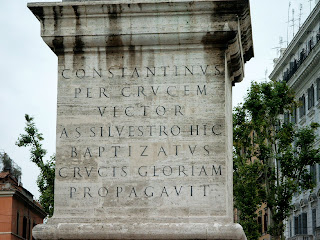

The first

obelisk had been transported from Egypt Rome Rome

The second

obelisk was transported from Luxor Egypt France 1833. In 1836 it was erected in the Place de

la Concorde in Paris

The third

obelisk was transported from Alexandria Egypt England 1878. In 1878 it was erected on the

Embankment of the River Thames. [See Cleopatra’s Needle, 1893]

The fourth

obelisk was transported from Alexandria Egypt US 1880. In 1881 it was erected in Central Park in New York

Engelbach

wrote his book almost one hundred years ago, but in my opinion it is still

relevant. If you are interested in ancient Egypt

on the granite in the ancient quarry.

The broken or unfinished obelisk seen from the top.

The ancient stone block is 137 feet long and weighs ca. 1,168 tons.

The unfinished obelisk.

The broken obelisk.

In this picture you can see one of several fissures in the granite.

The broken obelisk seen from the bottom.

Notice the group of visitors standing near the top of the monument.

This can give you an idea of the scale.

The broken obelisk seen from the bottom.

Notice the group of visitors standing near the top of the monument.

This can give you an idea of the scale.

* * *

The ancient stone block is 137 feet long and weighs ca. 1,168 tons.

The unfinished obelisk.

The broken obelisk.

In this picture you can see one of several fissures in the granite.

The broken obelisk seen from the bottom.

Notice the group of visitors standing near the top of the monument.

This can give you an idea of the scale.

The broken obelisk seen from the bottom.

Notice the group of visitors standing near the top of the monument.

This can give you an idea of the scale.

Figure 21 in Engelbach's book:

"Transport of

the statue of Dhuthopte, from his tomb at el-Bersheh."

Today this person is

known as Djehutihotep and the location as Deir el-Bersha.

Figure 24 in Engelbach's book:

"Boat of

Queen Hatshepsôwet from the Punt reliefs at Dêr el-Bahari."

Today the queen is

known as Hatshepsut and the location as Deir el-Bahari.

* * *