Atlas of Egyptian Art presents drawings and paintings made by the French 19th century Egyptologist Prisse d’Avennes during his first and second trips to

Maarten J.Raven and Oluf E. Kaper

are both Dutch Egyptologists, but their texts are written in English.

Emile

Prisse D’Avennes (1807-1879) was educated as an architect and engineer, but his

personal interest led him to become an Egyptologist. His first visit to Egypt Paris

A similar

project was undertaken by the Italian scholar Ippolito Rosellini, who visited Egypt Nubia

The

material in the Atlas is divided into five sections:

(1)

Architecture

(2)

Drawings

(3)

Sculptures

(4)

Paintings

(5)

Industrial Art

All

illustrations are interesting and valuable, because they document the condition

of the ancient monuments in the 19th century. Since then some

monuments have suffered further damage, and the colours of some paintings have

faded a great deal. But some of these illustrations are more than just interesting

and valuable; they are outstanding.

In fact,

they are so good that they are often used in modern books about ancient Egypt

* Pillars

of Thutmosis III decorated with a papyrus plant (symbol of Lower Egypt , the north) and with a lily (symbol

of Upper

Egypt , the

south); from Karnak : page 14.

* A column

decorated with patterns and hieroglyphs: from the Ramesseum: page 23.

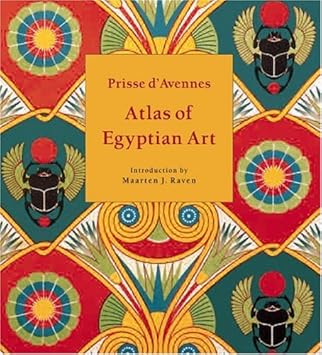

* A ceiling

pattern, which uses the winged scarab with a sun disc, symbolizing rebirth

after death (this image, from a tomb in the

necropolis of Thebes, is also used on the cover of the book)

* Three

ceiling patterns; two of them show two vultures, while the third shows a gaggle of

geese; from different locations: page 35.

* One of

two obelisks erected by Ramesses II in front of the Luxor Paris

* A sketch

representing Sethi I; from his tomb in the Valley of the Kings : page 67.

* The capture

of a fortress by Ramesses II; from the Ramesseum: page 79.

* A royal chariot;

from a tomb in Tell el-Amarna: page 84.

* Akhenaten

and his family; from two tombs in Tell el-Amarna: pp. 78 and 89.

* The small

temple at Abu

Simbel

dedicated to Nefertari and Hathor: page 99.

* Ramesses

II leading the Egyptian army in a battle against the Hittites; from the

Ramesseum: page 102.

* A portrait

of Ti and his wife: from the Mastaba of Ti, Sakkara : page 108

* A

portrait of Queen Tyti, probably a daughter of Ramesses III; from her tomb in

the Valley of the Queens : page 114.

* Five

scenes with people at work; from different locations: pp. 117-121.

* A

portrait of Ramesses II. Prisse d’Avennes copied this painting from a tomb

behind the Ramesseum in 1843. When he returned in 1859, the tomb had

disappeared: page 126.

* A

portrait of Merenptah; from his tomb in the Valley of the Kings : page 127.

* A portrait of Queen Nebtawy, daughter of

Ramesses II; from her tomb in the Valley of the Queens : page 128.

* A

portrait of Ramesses III; from his tomb in the Valley of the Kings : page 131.

Prisse

d’Avennes is often described with positive words. It is easy to understand why.

As Maarten Ravens says in his introduction:

“Prisse’s drawings, plans, and

reconstructions of well-known monuments excel in their meticulous precision and

daring originality and have lost nothing of their value.”

But not

everything about him is positive. Raven begins:

“This collection of works

demonstrates that Prisse was a remarkable scholar and an able draftsman.”

But then

he adds:

“Yet it cannot be denied that there was another side to his

personality; an exactingness and imperiousness, an unremitting scrupulosity and

a disdain for etiquette, that set him apart from his contemporaries.”

In

addition, he did something which was illegal and seems to go against everything

that he stands for: one night in May 1843 he entered the Karnak temple complex with a team of

workers and dismantled the so-called king list in the Hall of the Ancestors.

The blocks with the king list were placed in boxes, and the following year they

were smuggled out of the country and transported to France Paris

Champollion

did something similar during his expedition with Rosellini 1828-1829: during a

visit to the tomb of Sethi I in the Valley of the Kings he removed a part of the wall

decoration and took it with him to France

However,

the purpose of this review is to evaluate the book, and not the man. Raven

concludes his introduction with the following words:

“He was far

ahead of his time in his awareness of the vulnerability of the monuments and

the need to protect and record them… The present reprint of Prisse’s Atlas, the

plates of which have lost nothing of their value for modern Egyptology, is a

fitting tribute to the memory of the great orientalist.”

I agree

with him. The Atlas is a beautiful book. If you like ancient history, in

particular ancient Egypt

Papyriform columns of Thutmosis III in Karnak (18th dynasty) - page 21.

A column of the Ramesseum (Thebes) - page 23.

A ceiling pattern: a gaggle of geese from the new kingdom tomb of

Nebamun and Imiseba - page 35.

Nebamun and Imiseba - page 35.

A ceiling pattern: two vultures from the tomb of Bekenrenef - page 35.

A column of the hypostyle hall of Karnak (Thebes - 19th dynasty) - page 43.

A royal chariot (Tell el-Amarna - 18th dynasty) - page 84.

Ramesses II leading the Egyptian army in battle against the Hittites

(Thebes, Ramesseum - 19th dynasty) - page 102.

A portrait of Queen Tyti, probably a daughter of Ramesses III

(from her tomb in the Valley of the Queens) - page 114.

People at work: manufacturing gold and silver vases

(Necropolis of Thebes - 18th dynasty) - page 118.

People at work: transport of utensils and provisions

(Necropolis of Thebes - 18th dynasty) - page 120.

A portrait of Ramesses II as a young man (19th dynasty) - page 126.

A portrait of Queen Nebtawy

(a daughter of Ramesses II - 19th dynasty) - page 128.

* * *

No comments:

Post a Comment