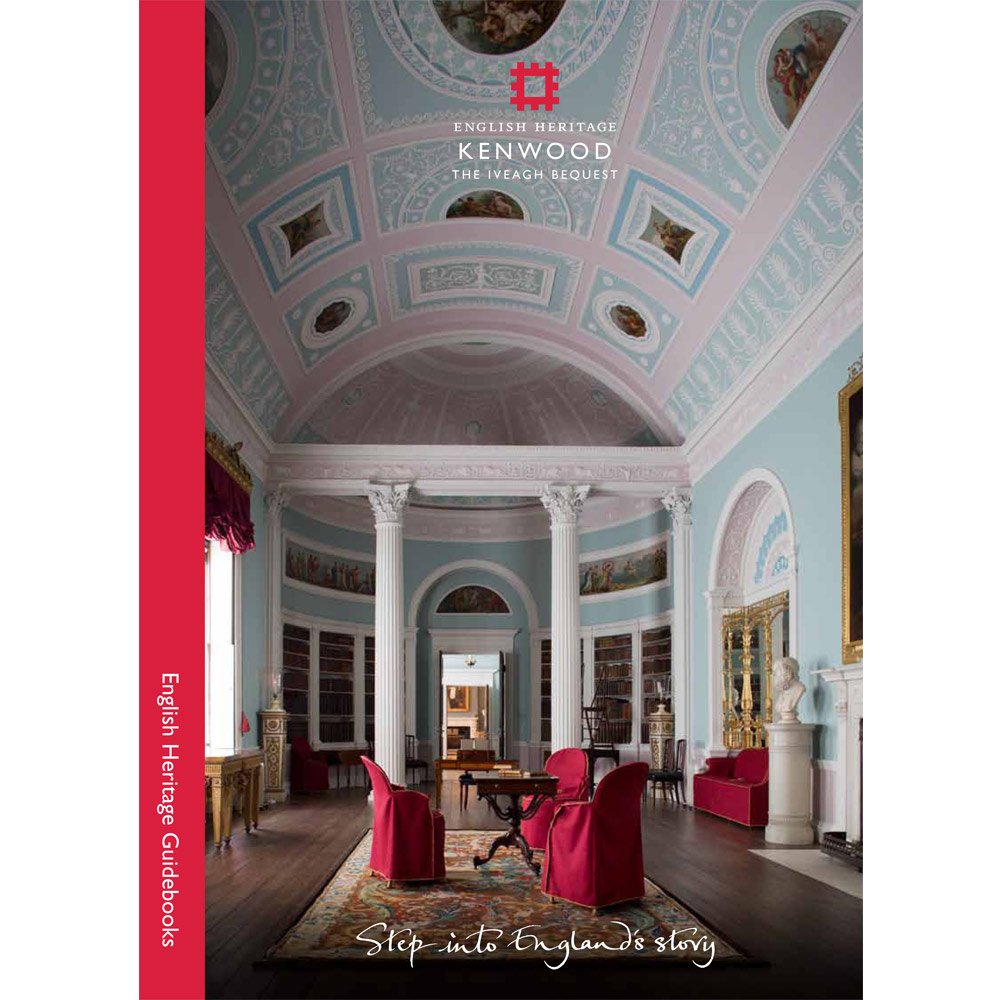

Kenwood: The

Iveagh Bequest by Laura Houliston and Susan Jenkins was published by English

Heritage in 2014. It is an excellent guidebook to Kenwood House, a neoclassical

villa, located in Hampstead, just north of London. The main text is divided

into three sections:

** Section one is

about the main building. The important rooms are presented, one by one, with

text and illustrations.

** Section two is

about the park. The major features of the park are presented, with text and

illustrations.

** Section three is

about the history of Kenwood. The owners and the architects who were

responsible for exterior and interior designs are presented, with text and

illustrations.

Spread throughout

the book there are ten separate sidebars (each of them gets one page) which

provide additional information about important events, significant persons, and

or famous paintings which are on display at Kenwood.

This slim volume

is published in a large format (21 x 28.5 cm). It is well-written,

well-organised, and well-illustrated. All modern photos are in colour. In 1913

Kenwood was presented in Country Life. Some of the photos that were taken

then are used here. While they are in black-and-white, they have great

historical importance, because they show us what the place looked like more

than one hundred years ago.

The layout of the

book is user-friendly:

** Inside the front

cover there is a flap you can fold out. A large drawing offers a bird’s eye view of Kenwood with the main building in the foreground,

the park in the centre, and the city of London in the background.

** Inside the back

cover there is another flap you can fold out. There are three floorplans of

Kenwood: below, the ground-floor plan; above, the first-floor plan and the

floorplan of the dairy, located west of the main building.

THE HISTORY OF

KENWOOD

The first house at

Kenwood was built by the king’s printer John Bill in 1616. It was a small

house. William Murray, a lawyer from Scotland, bought it in 1754 and turned it

into a stately home. He was Lord Chief Justice from 1756 and was created the

first Earl of Mansfield in 1776. Later earls made further additions and changes

to the villa, but they did not live there much. They preferred their residence

in Scotland, Scone Palace, near Perth.

By 1910, the sixth

Earl of Mansfield had decided to sell Kenwood. It did not happen at once, but

some furniture was sold at auction in 1922. In 1925 the first Earl of Iveagh –

Edward Cecil Guinness – bought the house. In that year the park was opened to

the public. Lord Iveagh died two years later; in his will he donated the house and

a part of his collection of famous paintings to the nation. That is why Kenwood

is described as the Iveagh Bequest. In 1928 the main building was opened to

the public.

Since 1986,

Kenwood has been administered by English Heritage. In 2012 it was closed for a

major restoration which lasted 18 months and cost almost six million pounds. It

was opened to the public again in late 2013. To mark the completion of the

restoration a new version of the official guidebook written by Laura Houliston

and Susan Jenkins was published in March 2014.

THE IMPORTANCE OF

KENWOOD

This estate is important,

not only because of the art and architecture it represents, but also because of

the people who are connected with it: the owners, the people who lived there,

the architects who designed the buildings, the people who rented it, and the

people who were invited to visit it while it was still a private home and not

yet a public museum. Here are some examples which are mentioned in the book:

** William Murray,

the first Earl of Mansfield or Lord Mansfield (1705-1793), bought Kenwood in

1754 and lived here with his family until his death in 1793. He was born in

Scotland, but moved to England where he became an important lawyer. He was Lord

Chief Justice for more than thirty years (1756-1788). In this capacity he ruled

in the case of Somerset in 1772 and the case of the Zong in 1783. These rulings

inspired the movement for the abolition of slavery.

** Robert Adam

(1728-1792) was a famous architect from Scotland, who worked in England. Lord

Mansfield hired him to change Kenwood into a stately home.

** Dido Elizabeth

Belle (1761-1804) was raised at Kenwood and lived here for almost thirty years

(1765-1793). Her father was a captain of the Royal Navy, John Lindsay. Her

mother was a black slave from Africa, Maria Belle. In 1765 his father brought

her to England and placed her with his uncle, Lord Mansfield.

** Lady Elizabeth

Murray (1760-1825) was the daughter of David Murray, known as the ambassador,

who became the second Earl of Mansfield in 1793. When her mother died in 1766,

her father placed her with his uncle, Lord Mansfield.

As you can see, there were two

young girls at Kenwood. The girls were cousins, actually half-cousins, but grew

up as sisters. There is a famous painting of them from 1779 when they were

almost twenty years old. The original was in Kenwood for many years. It was not

sold in the auction of 1922. Instead it was moved to Scone Palace in Scotland

where it remains to this day.

At Kenwood there

is a copy. It appears in the book on page 41. The painting of the two young

girls inspired an historical movie, the drama-documentary Belle about the

early life of Dido Elizabeth Belle that premiered at an international film festival in 2013; it was shown in theatres and released on

DVD in 2014.

While several scenes

of the film are set in Kenwood, they are not filmed there, because Kenwood was closed

for restoration from 2012 to 2013 while the movie was being shot.

** Thomas

Hutchinson (1711-1780) was a loyalist governor of Massachusetts for many years

(1758-1774). In 1774 he sailed to England where he lived for the rest of his

life. He visited Kenwood in 1779. Dido is mentioned in his diary.

** Michael Mikhailovich,

Grand Duke of Russia (1861-1929), was exiled from Russia in 1891, because he

married without permission from the imperial family. After a while he ended up

in England where he rented Kenwood from 1910 to 1917. After the Russian

Revolution of 1917 he lost his fortune, so he could no longer afford to live

there.

** King Edward VII

and Queen Alexandra visited Kenwood in June 1914 while the Grand Duke of Russia

was living there.

** Edward Cecil

Guinness, the first Earl of Iveagh or Lord Iveagh (1847-1927), made a fortune

selling beer. He spent a lot of his money on paintings. In 1925 he bought

Kenwood. He planned to make it a home for his collection of paintings. He also

planned to donate the house and his paintings to the nation.

When he died in 1927, the plans were not completed, but his wishes were carried out anyway. Kenwood and a part of his collection of paintings were donated to the nation. Since he had stipulated that there should be free access to his museum of art, you do not have to pay anything when you visit this place.

When he died in 1927, the plans were not completed, but his wishes were carried out anyway. Kenwood and a part of his collection of paintings were donated to the nation. Since he had stipulated that there should be free access to his museum of art, you do not have to pay anything when you visit this place.

** The famous painting of Dido and Elizabeth.**

MINOR FLAWS

As stated above,

this is an excellent book about Kenwood. I noticed only three minor flaws (for more details about the flaws, see the PS below):

# 1. David

Martin’s painting of Lord Mansfield is mentioned twice: on page 10 we are told this painting is

from 1776. But on page 39 the authors claim it is from 1775. This inconsistency

is puzzling.

# 2. Lady

Elizabeth Murray is mentioned on page 41. The authors claim she was born ca.

1763 and died 1823. Both dates are wrong. As stated above, Elizabeth Murray was

born in 1760 and died in 1825.

# 3. The Grand

Duke of Russia is mentioned on page 46. At first he is identified as “grandson

of Tsar Nicholas I and second cousin to the last Tsar Nicholas II.” But later

on the same page we are told that he was forced to sublet Kenwood in 1917,

“following the Russian Revolution and the murder of his brother the Tsar.”

The former

identification is correct, but the latter is not. The Grand Duke was not the

brother of the last Tsar, he was his second cousin. Moreover, the last Tsar

Nicholas II was murdered in 1918, not in 1917, as implied in the text.

CONCLUSION

Who is the target

audience of this book? I can think of two or three groups. If you are planning

a visit to Kenwood, this book is a useful tool to prepare your visit. If you

have already been there, this book will be a wonderful souvenir of your visit.

Perhaps you are an

armchair traveller. If you are interested in the history of the modern world,

in particular the history of art and architecture, I am sure you will enjoy

this slim volume about Kenwood from English Heritage.

PS # 1. For

information about Scone Palace near Perth in Scotland, see Scone Palace by

Jamie Jauncey (2015).

PS # 2. For

information about Lord Mansfield, see Lord Mansfield: Justice in the Age of

Reason by Norman S. Poser (2013, 2015).

PS # 3. For

information about the architect Robert Adam, see The Genius of Robert Adam by Eileen Harris

(2001) and Robert Adam by Richard John (2010).

PS # 4. For

information about Dido Elizabeth Belle, see Belle: The True Story of Dido

Belle by Paula Byrne (2014) and Dido Elizabeth belle: A Biography by Fergus

Mason (2014)

PS # 5. For

information about Dido, her father John Lindsay, and her mother Maria Belle in

Pensacola, Florida, see Historical Pensacola by John J. Clune and Margo

Stringfield (2009).

PS # 6. Since my review was written I have been in contact with English Heritage. They gave the following response to my list of flaws:

(A) David Martin made more than one painting of Lord Mansfield. The large painting mentioned in the text on page 10 is from 1776. The painting shown on page 39 (a smaller version) is from 1775, as stated in the caption. That is why both dates are correct! They say the fact that there are two paintings will be explained in the next edition of the book.

(B) The dates of Elizabeth Murray are wrong. They say the correct dates will appear in the next edition of the book.

(C) The Grand Duke was the cousin and not the brother of the Tsar. They say this mistake will be corrected in the next edition of the book. The text does not claim that the Tsar was murdered in 1917, but it is implied. Any confusion can be avoided by adding the dates: "... following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the murder of the Tsar in 1918."

PS # 6. Since my review was written I have been in contact with English Heritage. They gave the following response to my list of flaws:

(A) David Martin made more than one painting of Lord Mansfield. The large painting mentioned in the text on page 10 is from 1776. The painting shown on page 39 (a smaller version) is from 1775, as stated in the caption. That is why both dates are correct! They say the fact that there are two paintings will be explained in the next edition of the book.

(B) The dates of Elizabeth Murray are wrong. They say the correct dates will appear in the next edition of the book.

(C) The Grand Duke was the cousin and not the brother of the Tsar. They say this mistake will be corrected in the next edition of the book. The text does not claim that the Tsar was murdered in 1917, but it is implied. Any confusion can be avoided by adding the dates: "... following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the murder of the Tsar in 1918."

***

Laura Houliston

& Susan Jenkins,

Kenwood: The Iveagh Bequest,

English Heritage,

2014, 52 pages

*****

David Martin's painting of Lord Mansfield

This is the small painting from 1775

*****

*****

No comments:

Post a Comment