Belle is a 103-minute drama-documentary, which premiered at an international film festival in 2013; it was shown in theatres and released on DVD in 2014. Directed by Amma Asante, written by Misan Sagay, and produced by Damian Jones, this film is a period drama set in eighteenth-century England.

The lead character is the woman after whom the film is named: Dido Elizabeth Belle, a mulatto (half-black, half-white), who was raised in the household of a white aristocratic family.

The dramatized version of her life includes a love story and touches on several serious issues of the time such as power and privilege; class, gender and race; prejudice and tolerance, as well as the slave trade and slavery in general.

The cast includes the following:

** Dido Elizabeth

Belle (1761-1804) – played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw

** Elizabeth

Murray (1760-1825) – played by Sarah Gadon

** William Murray,

aka Lord Mansfield, the first Earl of Mansfield (1705-1793) – played by Tom

Wilkinson

** Elizabeth Murray,

his wife, aka Lady Mansfield (1704-1784) – played by Emily Watson

** John Lindsay,

Belle’s father (1737-1788) – played by Matthew Goode

** John Davinier,

son of a clergyman and Lord Mansfield’s legal assistant – played by Sam Reid

[Please note: there are some spoilers ahead. If you have not seen the film and you do not

want to know any details about it, stop reading now. If you have seen it or you

want to prepare yourself for it, you should continue reading.]

THE PLOT

Belle’s mother was

Maria Belle, a black slave from Africa. Her father was John Lindsay, a white

man from England, who was a captain in the Royal Navy. John met Maria while he

was stationed in the Caribbean. As a young child, Belle was brought to England by

her father who placed her with his uncle, Lord Mansfield, an important and

powerful aristocrat. He was Lord Chief Justice of England for more than thirty

years (1756-1788). In the beginning of the film Belle and her father arrive at Kenwood House in Hampstead, north of London. Lord Mansfield and his wife are shocked when they realise Belle is black, but they decide to take her in anyway because she is after all the daughter of Lord Mansfield’s nephew.

When Belle arrives, another young girl is already living at Kenwood House: Elizabeth Murray, the daughter of David Murray, another nephew of Lord Mansfield. David had married Henrietta in 1759 and they had one daughter – Elizabeth – in 1760. When Elizabeth’s mother died in 1766, her father placed her with his uncle, Lord Mansfield, the first Earl of Mansfield. Later, David Murray would be the second Earl of Mansfield.

The two girls are

cousins, actually half-cousins, but grow up as sisters. Both are treated as

members of the family, but because of her colour, Belle is not allowed to sit

at the dinner table when there are guests in the house. She is, however,

allowed to join family and guests after dinner. Her status is difficult to

define. As she says in the film:

“How can I be too high of

rank to dine with the servants, but too low of rank to dine with my own family?”

When Elizabeth and

Dido are almost twenty years old, Lord Mansfield decides to commission a

portrait of them. In the film we see how they have to sit for the painter,

first Elizabeth and later Dido.

Around the same

time Lady Mansfield says it is time to start looking for a suitable husband for

Elizabeth. She and her husband agree that it is not possible to find a suitable

husband for Dido, because of her colour.

While these things

are going on, Lord Mansfield is working on a case that involves a cargo-ship -

the Zong - that was transporting slaves from Africa to the Americas in 1781.

Before reaching its final destination, the captain and the crew decided to

throw more than one hundred slaves overboard, because they were sick and weak

and they would not fetch a good price on the market. Officially, they were

dumped in order to save the crew and the rest of the cargo (the healthy and

strong slaves), because there was not enough water on board.

Later the ship’s

owner contacted his insurance company. He wanted compensation for the cargo

that had been “lost” on the voyage. When the insurance company refused to pay, the

ship’s owner decided to go to court.

[Please note: the

company is not being sued for murder; the question is

quite different: can the company be compensated for lost cargo? This fact is a

sign of the times.]

In 1783, this case

lands on Lord Mansfield’s desk. He must study the case and issue a ruling. In

order to speed things up, he decides to hire a young man as his legal assistant.

His name is John Davinier. In the film he is presented as the son of a

clergyman who wants to become a lawyer. He is also an ardent abolitionist. He

wants Lord Mansfield to rule against the ship’s owner, because he is opposed to

the slave trade and to slavery in general.

When Dido hears

about the case, she begins to take an interest in it. She also begins to take

an interest in the young man, although at first she is not ready to admit this

to anyone, not even to herself. He seems to feel the same way. He sees her as a

person. The colour of her skin does not matter to him. Thus the stage is set

for the love story between Dido and Davinier.

Lord Mansfield

does not want to discuss the case with Dido and he does not want Davinier to

discuss it with her either. He fires him, in order to keep them apart, but the

young man and the young woman cannot be stopped: they have a common interest in

the case and a growing interest in each other. They decide to meet in secret.

We can guess where this is going. After a while, Lord Mansfield gives them his

blessing, and so we can have a happy ending for Dido and Davinier.

THE PAINTING

According to the

people behind the film – Amma Asante, Misan Sagay and Damian Jones – it was

inspired by the painting of Dido and Elizabeth which is on display at Scone

Palace near Perth, in Scotland, the birthplace of Lord Mansfield. The unsigned painting was previously attributed to the German artist Johann Zoffany (1733-1810), but today this idea has been rejected. Perhaps it was painted by the Scottish artist David Martin (1737-1797), who did a portrait of Lord Mansfield (ca. 1775).

Amma Asante, the director of Belle, explains why the

painting inspired her film:

“You see a biracial girl, a woman of colour, who’s

depicted slightly higher than her white counterpart. She’s staring directly

out, with a very confident eye. This painting flipped tradition and everything

the 18th century told us about portraiture. What I saw was an opportunity to

tell a story that would combine art, history and politics.”

The painting was completed

in 1779 when the cousins were almost twenty years old. It remained at Kenwood

House until 1922 when it was moved to Scone Palace in Scotland, where it

remains to this day.

When the painting is

shown in the film [at 1.24], it has been modified in two ways. First, the faces

of the modern actresses have replaced the original faces of Dido and Elizabeth.

Secondly, Dido’s curious gesture pointing to her cheek has disappeared. Nobody

knows what the gesture means.

The original

painting is shown at the end of the film [at 1.38].

While the two

young women are presented at the same level, there is a subtle difference

between them. Elizabeth is sitting, she has a book in her left hand, perhaps to

give her an intellectual quality, and she is not moving. But her right arm

reaches out to Dido. Perhaps because Dido is running away from her. Maybe she

wants to say: “Don’t go! Stay here!”

Dido is wearing a turban

(something exotic); in her left hand she is holding a basket with fruits, and

she has a forward movement. She is not sitting. The index finger of her right

hand is pointing to her cheek. Perhaps she wants to say: “I am still here.” The

people behind the film did not like the curious gesture. In the modified

version of the painting it has been removed. I understand they had to change

the faces. This is a legitimate decision. But why remove the gesture? There was

no need for this change.

HISTORICAL

ACCURACY

The film is

inspired by a painting and based on a true story. But we do not know many details

of Dido’s life. Our information is limited. For the filmmakers this can be a

blessing. They can fill in the gaps with whatever they like, as long as their

ideas fit the few facts that we have. Unfortunately, they did not work in this

way. For them it was not enough to fill in the gaps. They decided to change the

known facts in order to fit their own ideas about Dido and her surroundings.

While a large part

of what we see and hear in this film is true, not everything is historically

correct. Even basic facts have been changed. In fact, the concept called

artistic license has been used in many ways from the beginning to the end of

the film, and the result is not always an improvement. Here are some examples:

** THE CHRONOLOGY.

The film opens with a brief message: “The year is 1769. Britain is an empire

and [London is] a slave-trading capital.” The year given here is puzzling. Dido

was born in 1761 and came to England in 1765. She was baptized in 1766 when she

was five years old. According to the film, she arrives is England in 1769 when

she is 8 years old, but this is not true. Why start out by giving us a wrong

year? As far as I can see, this change does not serve any purpose at all.

** DIDO’S MOTHER. In

the film we are told that Dido’s mother is dead and this is the reason why her

father brings her to his uncle in England. But this is not true. Maria Belle

was born around 1746 and died after 1781. Recent research by Margo Stringfield,

an archaeologist from the University of West Florida, shows Maria Belle was

living in Pensacola, Florida, in the 1770s, and that John Lindsay had bought this

house for her. Why did he bring his daughter to England? Perhaps he hoped she

would have a better life there. We do not know. But the point is Maria Belle did

not die in 1765 when Dido was four years old.

** DIDO’S FATHER.

In the film we see him as he brings Dido to Kenwood House. After this we never

see him again. When Dido is a teenager, about 18, Lord Mansfield informs her

that her father has died. If she is 18, we are in 1779, but John Lindsay did

not die in that year. He lived until 1788, when Dido was 27. The chronology of

events has been changed. For no obvious reason.

** DIDO’S ECONOMIC

SITUATION. In the film, Dido inherits a large amount of money from her father: £

2,000 per year. Suddenly, she

is a wealthy woman; she does not have to marry. However, this is not true. John

Lindsay had three children with three different women. He was married to a

fourth woman, with whom he had no children. In his will he donated £ 1,000 to

the other two children, but he gave nothing to Dido, perhaps assuming Lord

Mansfield would provide for her. This assumption turned out to be true. When

Lord Mansfield died in 1793, Dido learned that his will gave her a one-time

payment of £ 500 plus an annuity of £ 100, but John Lindsay could not know this

when he made his will.

** ELIZABETH’S

ECONOMIC SITUATION. In the film, Elizabeth is penniless, because her father has

donated all his assets to his second wife. This means that it is difficult for

her to find and marry a man of high standing. In the film, a suitor withdraws

his interest as soon as he discovers that she has no fortune. In the film, Dido

has money, while Elizabeth does not. In the real world, the situation was the

opposite. In addition, the economic disparity between the cousins is used to

cause a rift between them. There is no basis for this story-line. Elizabeth was

not penniless and she did find a husband. In 1785, when she was 25, she married

George Finch-Hatton, and they had three children (as stated in a message at the

end of the film).

** LORD

MANSFIELD’S LEGAL ASSISTANT. In the film, John Davinier is the son of a

clergyman who wants to be a lawyer. In the real world he was a servant. It is

not known if he was an abolitionist, but he did marry Dido in 1793, shortly after the

death of Lord Mansfield. A message at the end of the film states that they had

two sons. In fact they had three sons. Two twins born and baptized in 1795, and

one son born in 1800 and baptized in 1802.

** THE LEGAL CASE.

Lord Mansfield ruled on two cases which concerned the slave trade and slavery.

The first is about Somerset in 1772; the second about the Zong in 1783. In the

film, the first case is never mentioned. But when he gives his ruling on the

second case, his words are taken from his ruling on the first case eleven years

before. In this way the film combines the two cases without telling us about it.

In the film, Lord

Mansfield declares that the insurance company does not have to pay compensation

to the owner of the ship. Dido and Davinier are ecstatic when they hear the

verdict. In the real world, Lord Mansfield did no such thing; he merely ordered

a new hearing based on additional evidence. Apparently, the real verdict was not

strong enough for the filmmakers, so they decided to improve the facts and turn

the conservative judge into an ardent abolitionist, even though he had no

intention of confronting the elite whose fortunes were based on the slave trade

and slavery.

** PUBLIC OR

PRIVATE? In the final scene, outside the courthouse, Lord Mansfield gives the

young couple his blessing and drives away in his carriage. Dido and Davinier

embrace and kiss each other, even though they are standing in a public place.

The real Dido and Davinier would never have done this. They would have waited

until they were in a private place. I understand the filmmakers want us to feel

happy for them, but the scene is a serious violation of the norms and customs

which applied in eighteenth-century England. It is an anachronism. With this scene we are suddenly

carried into the twentieth or the twenty-first century. This is stretching the

artistic license more than is acceptable.

THE IMPORTANCE OF

DIDO

This film does not

claim that Dido’s presence in Kenwood House influenced Lord Mansfield when he

wrote his rulings on Somerset in 1772 and on the Zong in 1783. If anything,

this film claims the opposite, because the Mansfield on the screen does not

want to talk to Dido about his case and he does not want his assistant to talk

to her about it either. He fires Davinier in order to keep them apart and to

prevent her from learning more about it. He does not succeed with these

measures, but that is beside the point. No matter what the film says and no matter what the historical evidence says, it is extremely interesting that the Lord Chief Justice of England had a relative who was half-black and half-white in his household. Dido was raised in Kenwood House and lived there for almost thirty tears. She was not treated exactly as her white cousin, there were small differences, but she was not treated as a slave or as a servant. Given the norms and customs which applied among the aristocracy in eighteenth-century England, her presence in this family and the privileges she enjoyed amount to a small revolution.

Lady and Lord

Mansfield did not have any children of their own. By all accounts they were

happy to have the cousins in their house. Having Dido and Elizabeth together

year after year could have made an impression on the man of the house and could

have made him question the laws which stated that white people were superior to

all others. Dido was an outsider in England. So was Lord Mansfield: he was

Scottish, not English; he was Catholic, not Anglican; he was not the first son

of his family, but he made a fortune for himself as a lawyer.

Lord Mansfield did

not want to rock the boat, he did not want to challenge the system that was

based on the slave trade and slavery. But if his rulings were not

revolutionary, they inspired others who wanted to rock the boat, who wanted

to challenge the system – people such as Granville Sharp (1735-1813) and

Olaudah Equino (1745-1797).

The rulings on

Somerset in 1772 and on the Zong in 1783 fuelled a movement that would lead to

the UK abolition of the slave trade in 1807 and the UK abolition of slavery in

a gradual process that began in 1833 (to be completed by 1840). This is what

the makers of Belle imply and who can blame them for this?

CONCLUSION

As stated above,

this film is inspired by a painting and based on a true story. The painting is

a wonderful piece of historical evidence. The few facts that we have about Dido

point to a character who grew in more than one way while she lived at Kenwood

House: she grew up to be young woman, but that was not all: she also became

aware of her own background and developed a confidence that would support her

through the rest of her life which (sadly) ended in 1804.

I can understand

why Amma Asante, Misan Sagay, and Damian Jones wanted to make this film. I can

understand why the actors chosen wanted to be in this film. The combination of

Dido – half-black and half-white, daughter of a slave from Africa – and Lord Mansfield

– the Lord Chief Justice of England who has to rule on cases regarding the

slave trade and slavery – is fantastic, incredible. Sometimes the true

historical facts will outdo even the most creative minds.

The film was well

received by professional critics and by the general public. On Rotten Tomatoes

it has a rating of 83 per cent. On IMDb it has a rating of 74 per cent. On

Metacritic it has a rating of 64 per cent.

I like this film.

I would like to give it five stars, but I cannot do this. I have two main

objections. The first objection

concerns the violations of historical accuracy already explained above. I do

not understand why the filmmakers felt they had to embellish the true story. The second objections

concerns the dialogue. Sometimes the dialogue is too stilted, and the lines

written for the actors are not always good enough.

For instance, when

Davinier has to explain why he is against slavery, he says a lot of words, but

it is not easy to understand what he says. If I cannot understand, I am not

convinced. Davinier and his abolitionist friends are not credible, because

their speech is too complicated.

While there is

much to like here, I cannot accept everything I see and hear. This movie is quite

good, but not great. I must take off one star for the first objection and

another star for the second objection. The conclusion is a rating of three

stars.

PS # 1. For

information about the life and times of Dido, see Dido Elizabeth Belle by

Fergus Mason (2014) and Belle by Paula Byrne (2014). Some reviewers of these

books complain that they offer too little information about the main character

and too much information about the slave trade and slavery in general.

PS # 2. For

information about the first Earl of Mansfield, see Lord Mansfield: Justice in

the Age of Reason by Norman S. Poser (2015)

PS # 3. For

information about the infamous slave-ship, see The Zong by James Walvin (2011).

The massacre of the slaves on the Zong is the subject of a famous painting called

The Slave Ship by the British artist J. M. W. Turner, first exhibited in

1840.

PS # 4. For

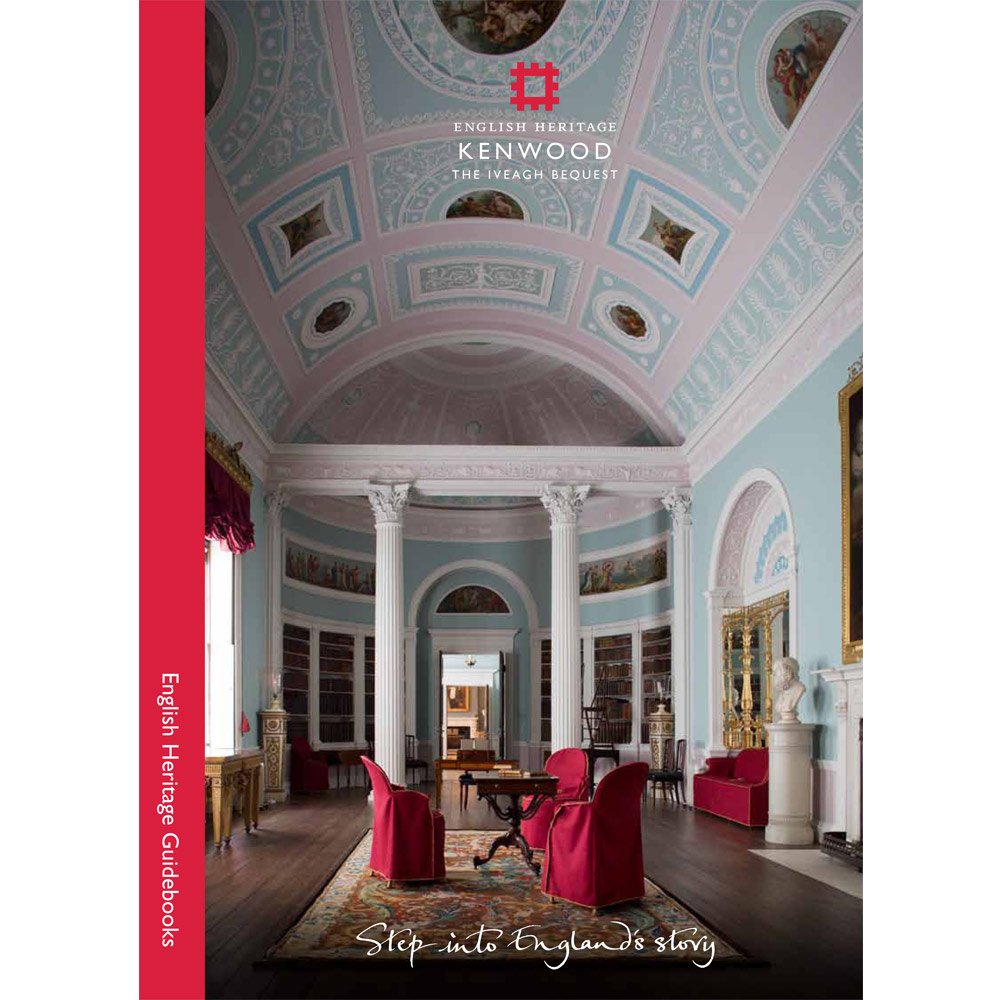

information about the manor in Hampstead, see Kenwood: The Iveagh Bequest by Laura Holiston

and Susan Jenkins (English Heritage in 2014). Several scenes of

the film are set in Kenwood, but they are not filmed there, because Kenwood was closed for major restoration from 2012 to 2013 while the film was being shot.

PS # 5. For information about the castle near Perth in Scotland, see Scone Palace by Jamie Jauncey (2015).

PS # 6. For

information about Dido, her father John Lindsay and her mother Maria Belle in

Pensacola, Florida, see Historical Pensacola by John J. Clune and Margo

Stringfield (2009).

PS # 7. The

following articles about Dido and the film are available online:

** Gene Adams,

“Dido Elizabeth Belle: A black girl at Kenwood,” Camden Historical Review, vol.

12 (1984), pp. 10-14

** “The little

girl who helped end slavery in Britain,” Georgian London, 6 November 2009

** Christine

Kenyon Jones, “Ambiguous cousinship,” Persuasions online, vol. 31, no.1, winter

2010, published by the Jane Austen Society of North America

** T. J. Holmes,

“Belle: A lesson about British slavery buried in a love story,” The Root, 9

April 2014

** Henry Louis

Gates, Jr., “Who was the real Dido Elizabeth Belle?” The Root, 26 August 2014

** Stuart

Jeffries, “Dido Belle: the art-world enigma who inspired a movie,” The

Guardian, 27 May 2014

** Alex von

Tunzelmann, “Belle: was British history really this black and white?” The

Guardian, 11 June 2014

** Maria Puente,

“Movie inspired by a painting, Belle is a true story,” USA Today, 5 May 2014

** Maria Puente,

“Taking a few liberties with the real story of Belle,” USA Today, 5 May 2014

** Steven W. Thomas,

“The assurance of Belle, the insurance of the Zong, and the speculation of

Cinema,” Film and Media, 12 June 2014

** BBC, “Historian

at the movies: An interview with James Walvin,” History Extra, 2 July 2014.

James Walvin – author The Zong - is asked

to evaluate the film: for enjoyment, he offers 1 star out of five; for

historical accuracy, he offers 2 stars out of five. In my opinion, this rating

is extremely harsh.

***

Belle,

Directed by Amma

Asante,

Produced by Damian

Jones,

Written by Misan

Sagay,

Run time: 103 minutes,

Premiere: 2013

***

***